Dance in and for Communities

The dances we used to have at the UNIA — they were fantastic! Every Thursday night, of course, at the hall there’d be a dance. Every Thursday night — that was the night that the domestics got off … The parents would act as chaperones, and they’d sit around if they didn’t dance. They came and they sat there and enjoyed themselves watching the younger people dance.

— Gwen Johnston

In No Burden To Carry: narratives of black women working in Ontario 1920-1950 (1991)

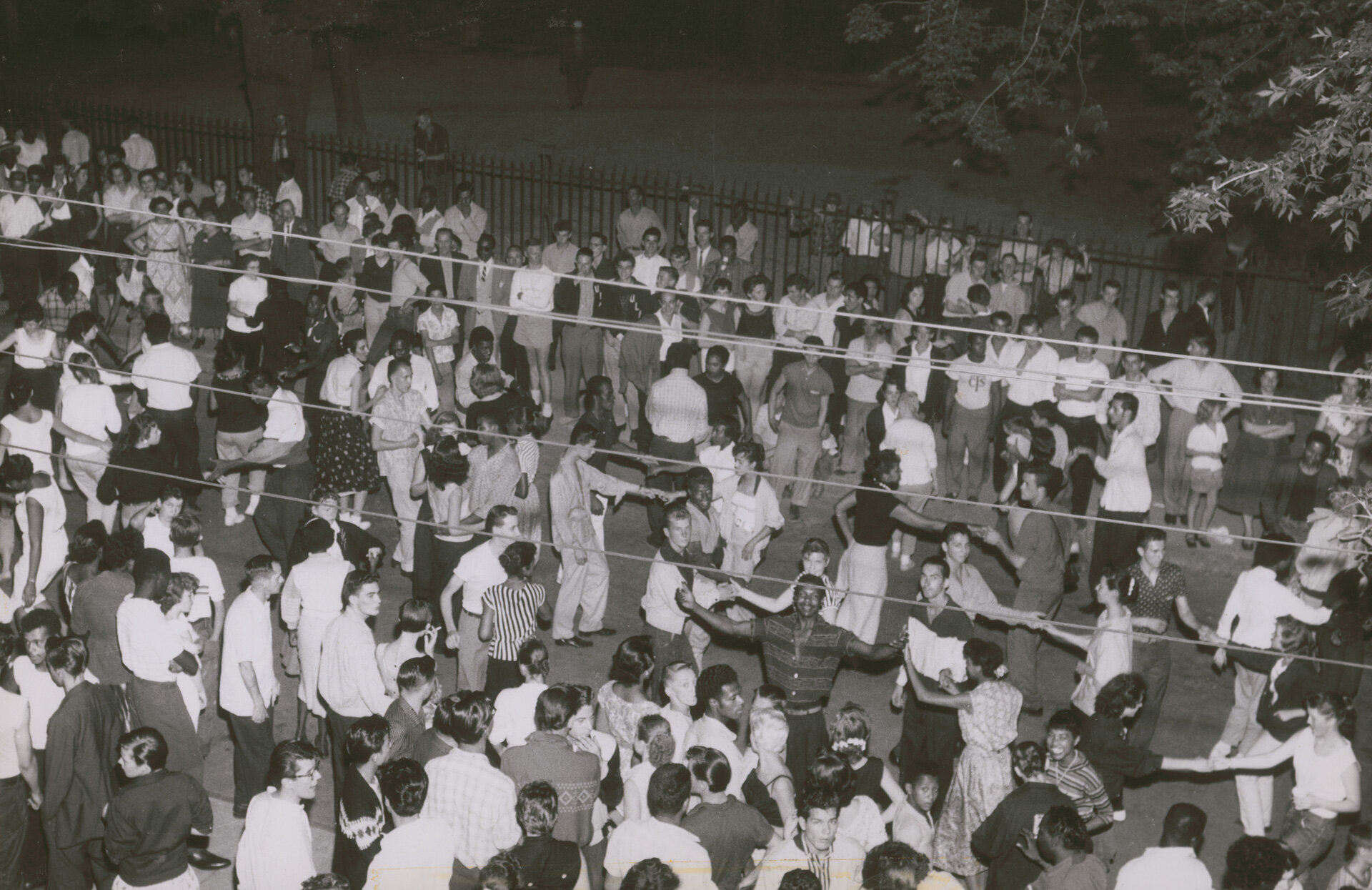

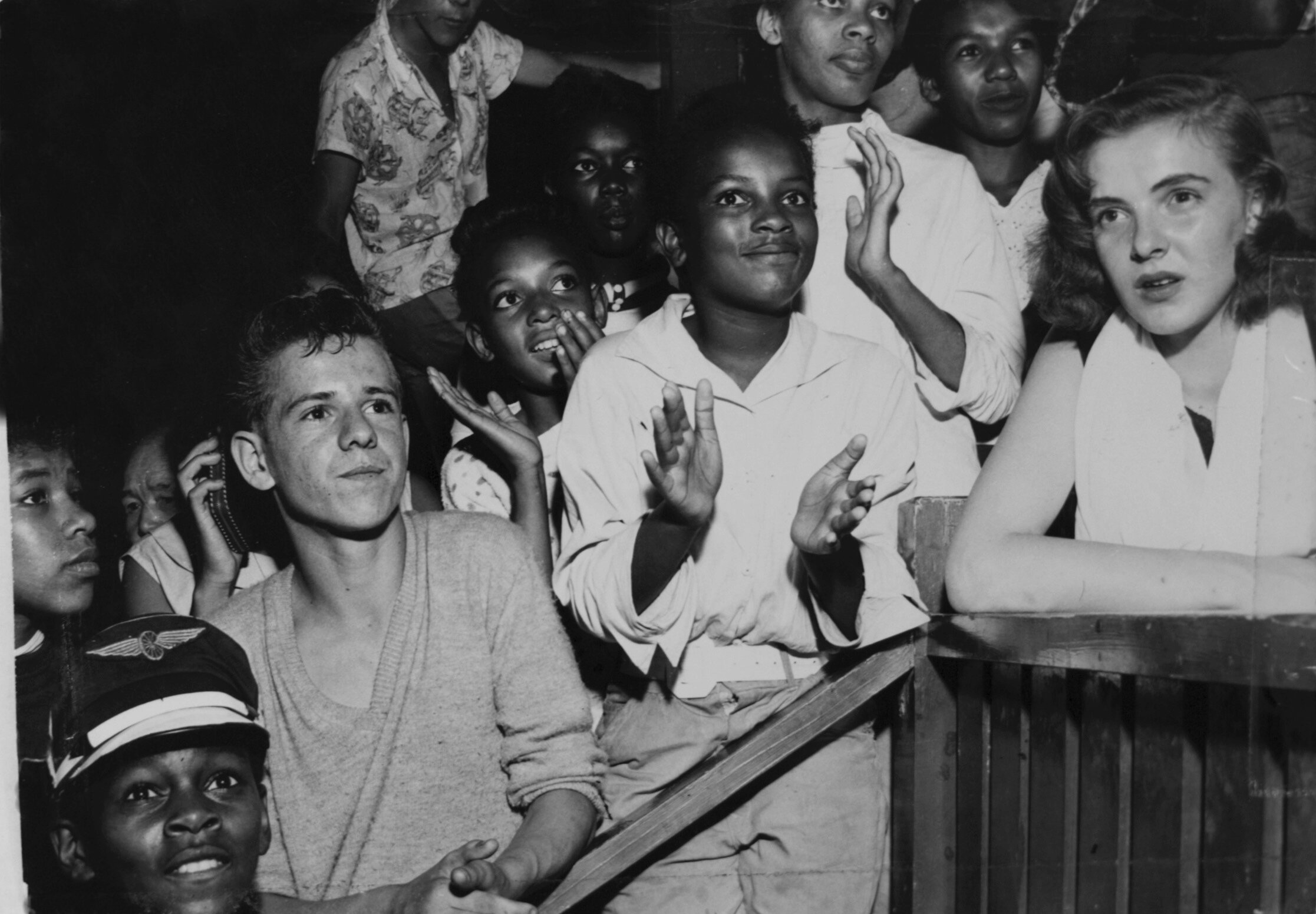

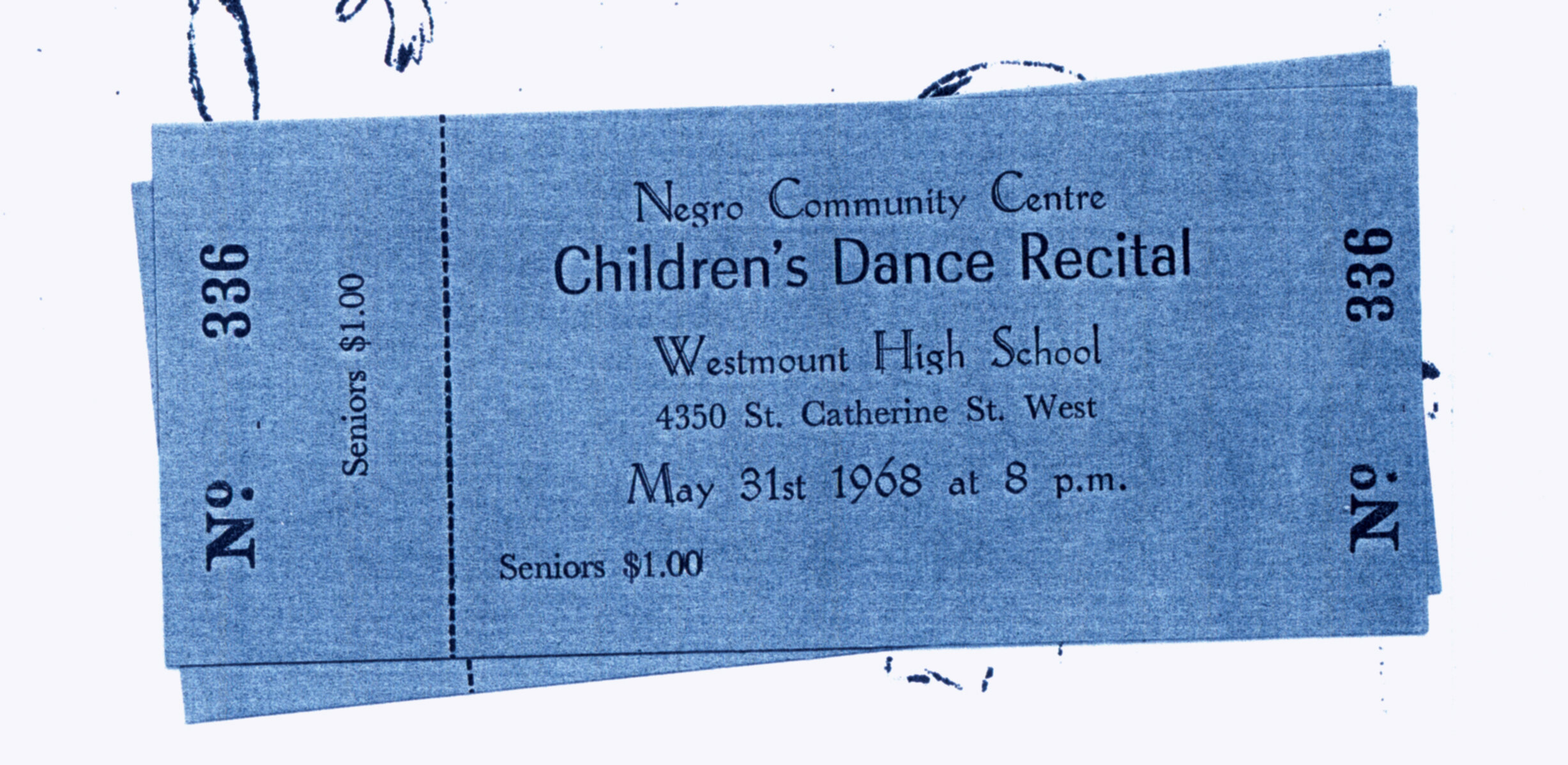

The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) — Toronto chapter is an example of community organizations that hosted social dances for and/or open to the Black population. Other venues included UNIA chapters in Montreal and Glace Bay, Nova Scotia; the Home Service Association (Toronto); the Negro Community Centre (Montreal) and University Settlement House (Toronto). Although each of these advocacy organizations had different mandates, social dances were common to them all.

While the majority of Black women worked in domestic service, many Black men worked as sleeping car porters for Canadian Pacific and Pullman Railways. Constant travel created a circuit between Winnipeg, Toronto and Montreal and into the United States through Detroit, Chicago and south to New Orleans. This resulted in the import of African-American cultural materials including newspapers, hair products, clothing and music. Porters supplied rhythm and blues, and rock and roll records that were not otherwise available in Canada. In Toronto, a small number of people had large vinyl collections that they would bring to the different dances.

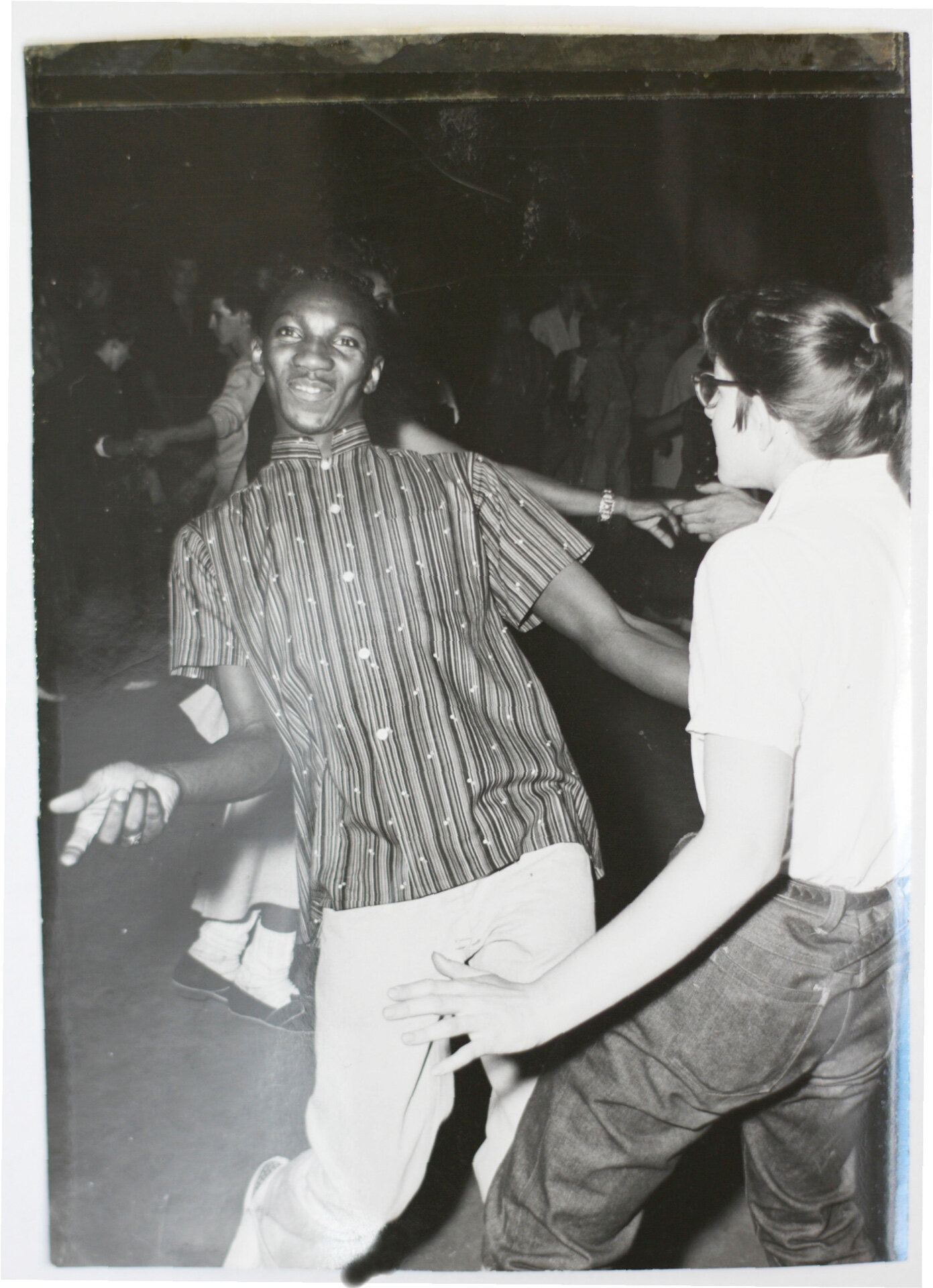

By mid-century, many dances were integrated racially. While this may have been acceptable on the dance floor, it did not reflect attitudes held by society at large and should not be considered an indication that Canada was without prejudice against interracial dating and marriage. These alternative spaces created what were intended as safe spaces for Black and other people marginalized due to their racialized backgrounds, class, religion or other factors.

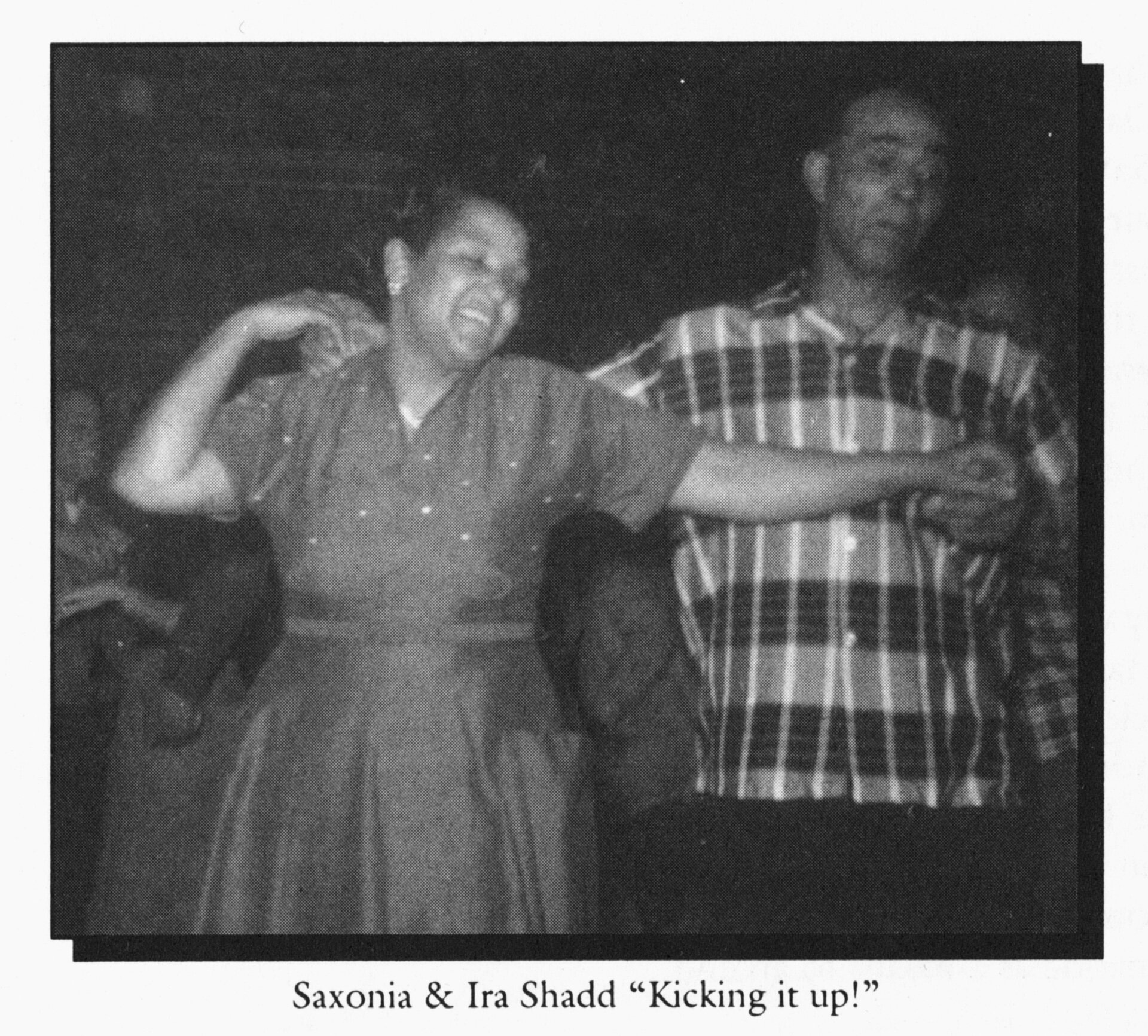

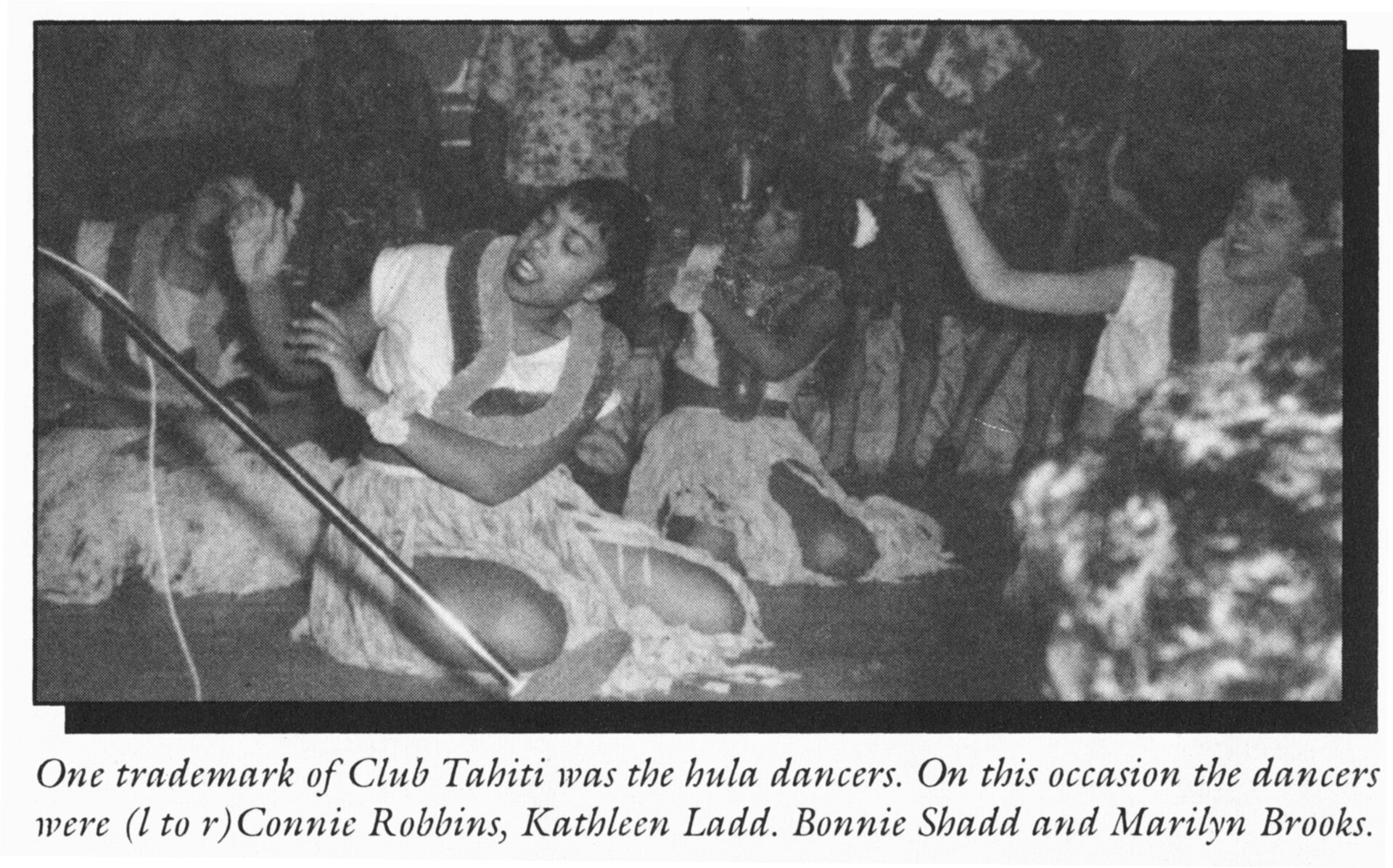

Annual Emancipation Day Picnics and popular night clubs, such as the Harlem Nocturne (Vancouver), Rumboogie Inn (Winnipeg) and Rockhead’s Paradise (Montreal), provided other popular sites for dancing. Class, religion, gender, cultural background and generation also impacted who attended which dances and where. Discrimination within the Black community itself is also revealed through examining social dance culture. Many of the older generation frowned upon dancing due to feelings that it was both sacrilegious and perpetuated stereotypes brought about by the minstrel show.

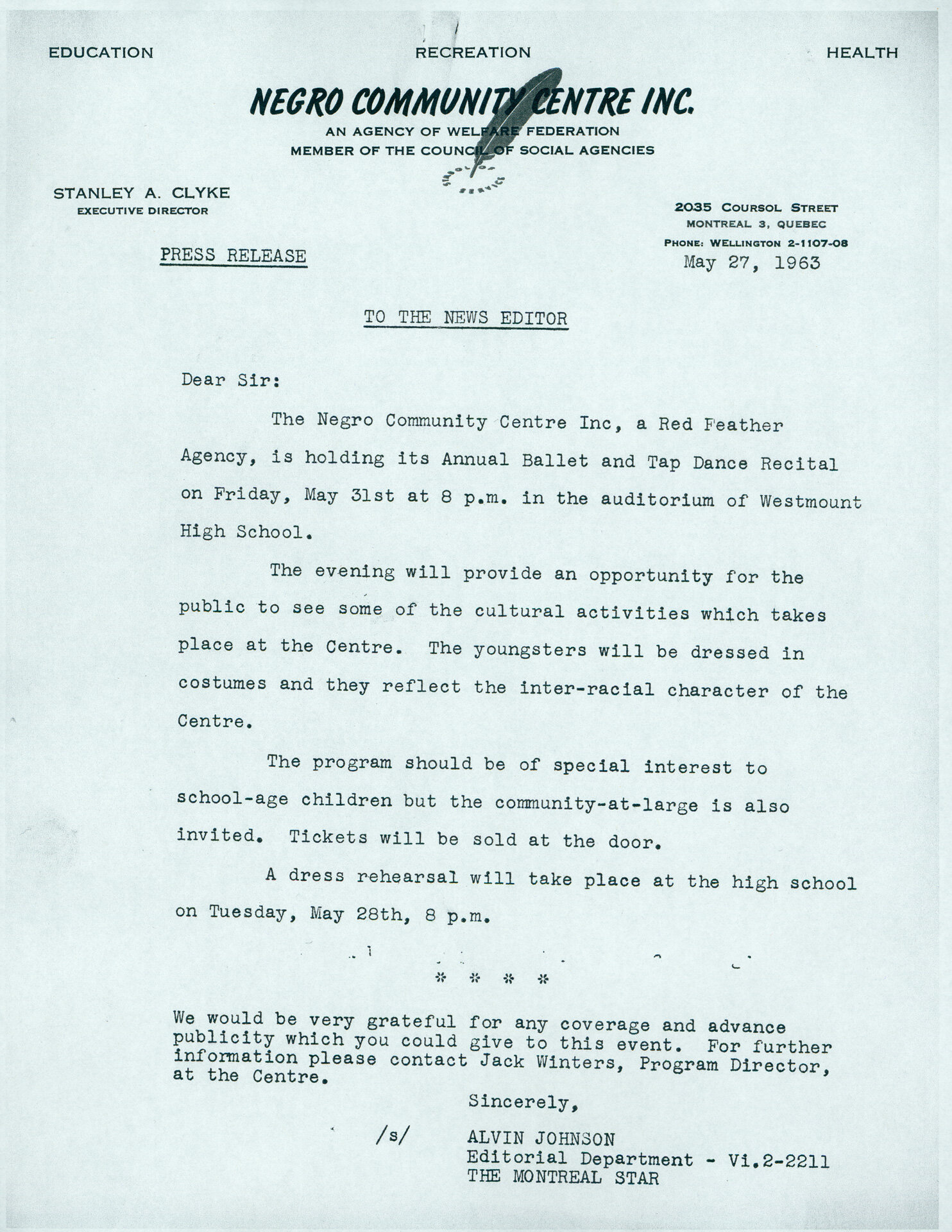

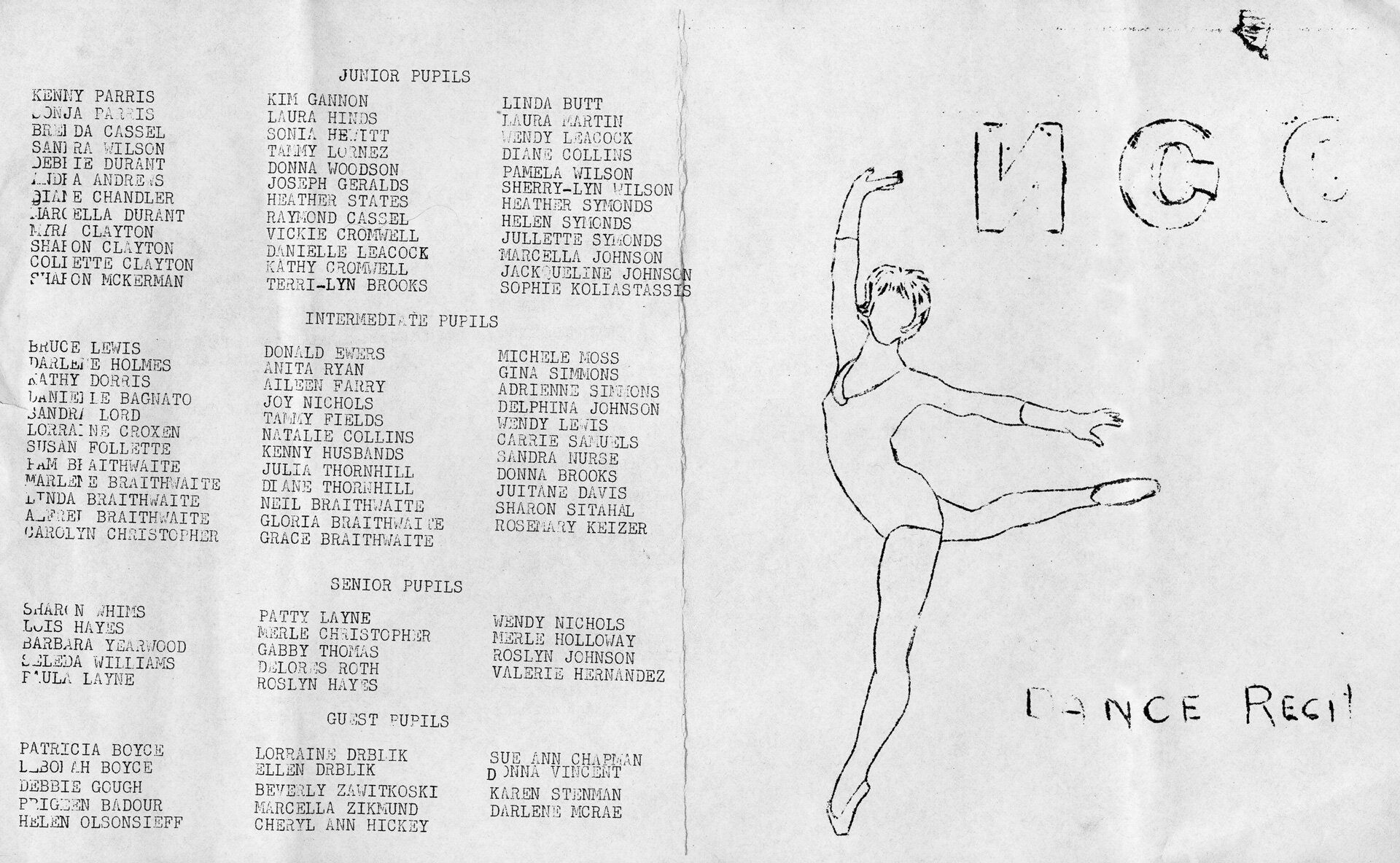

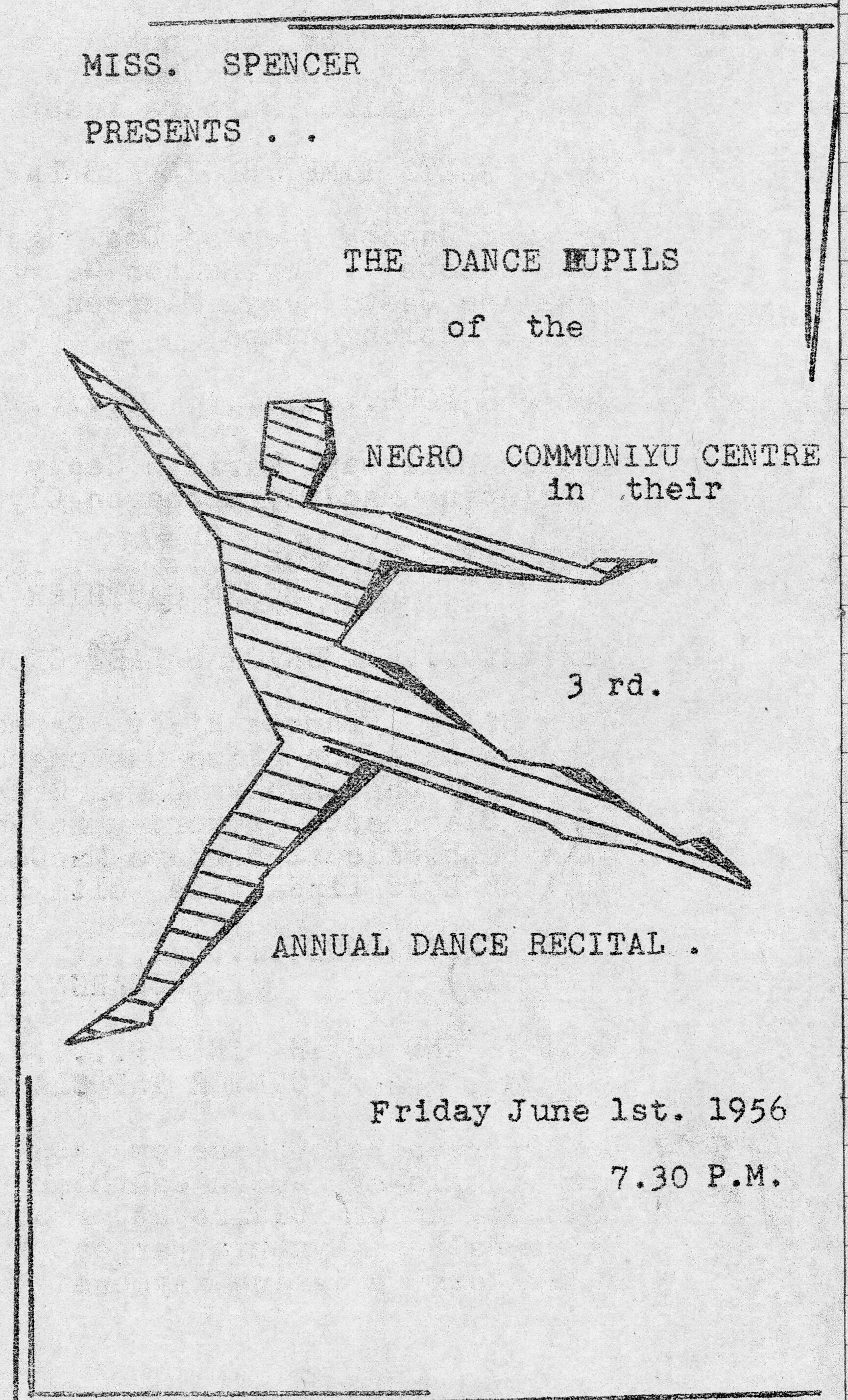

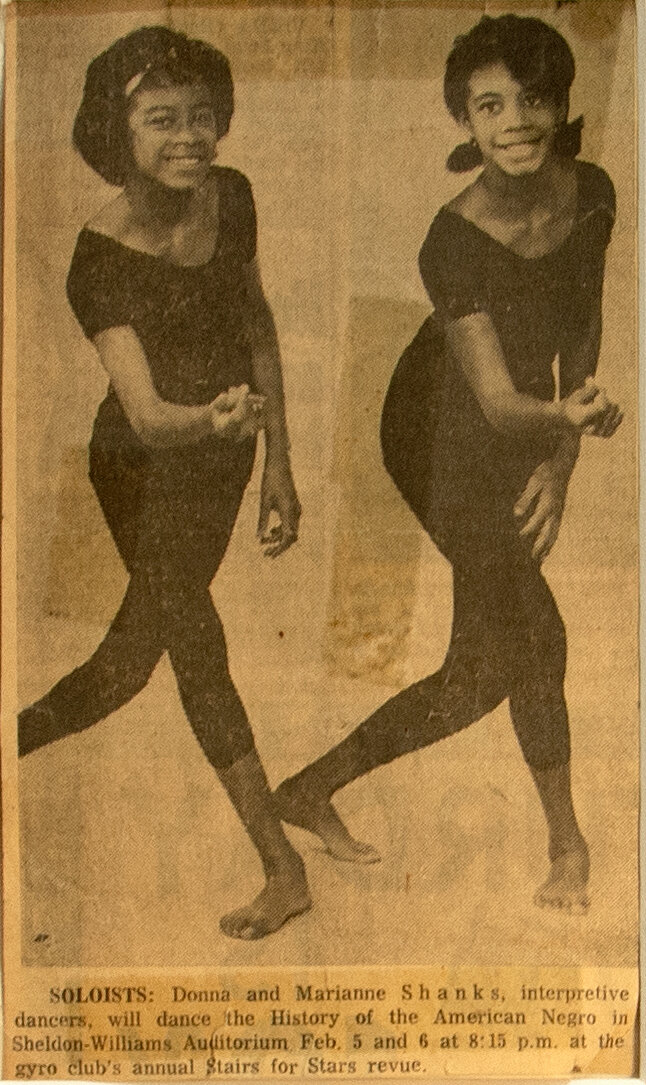

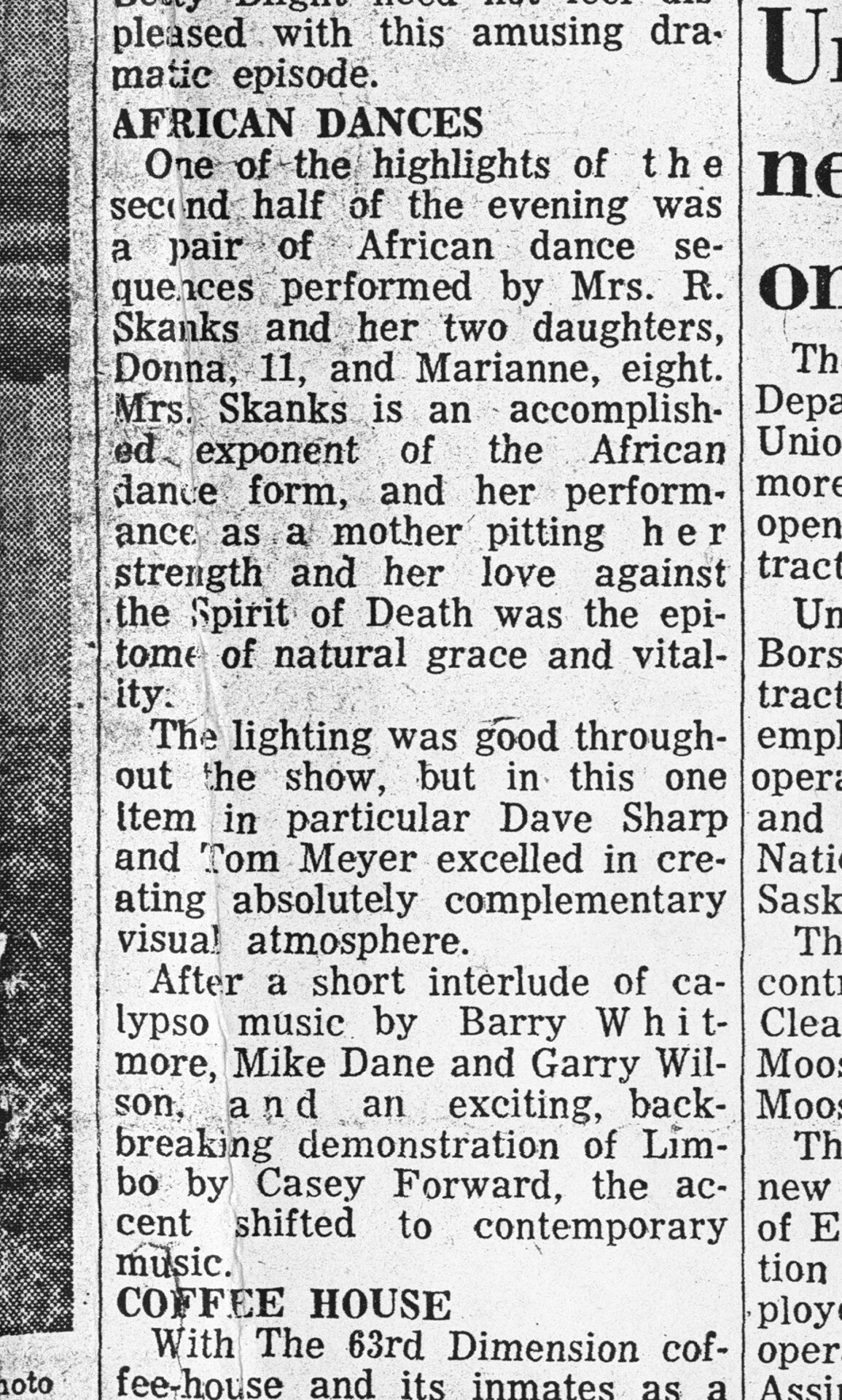

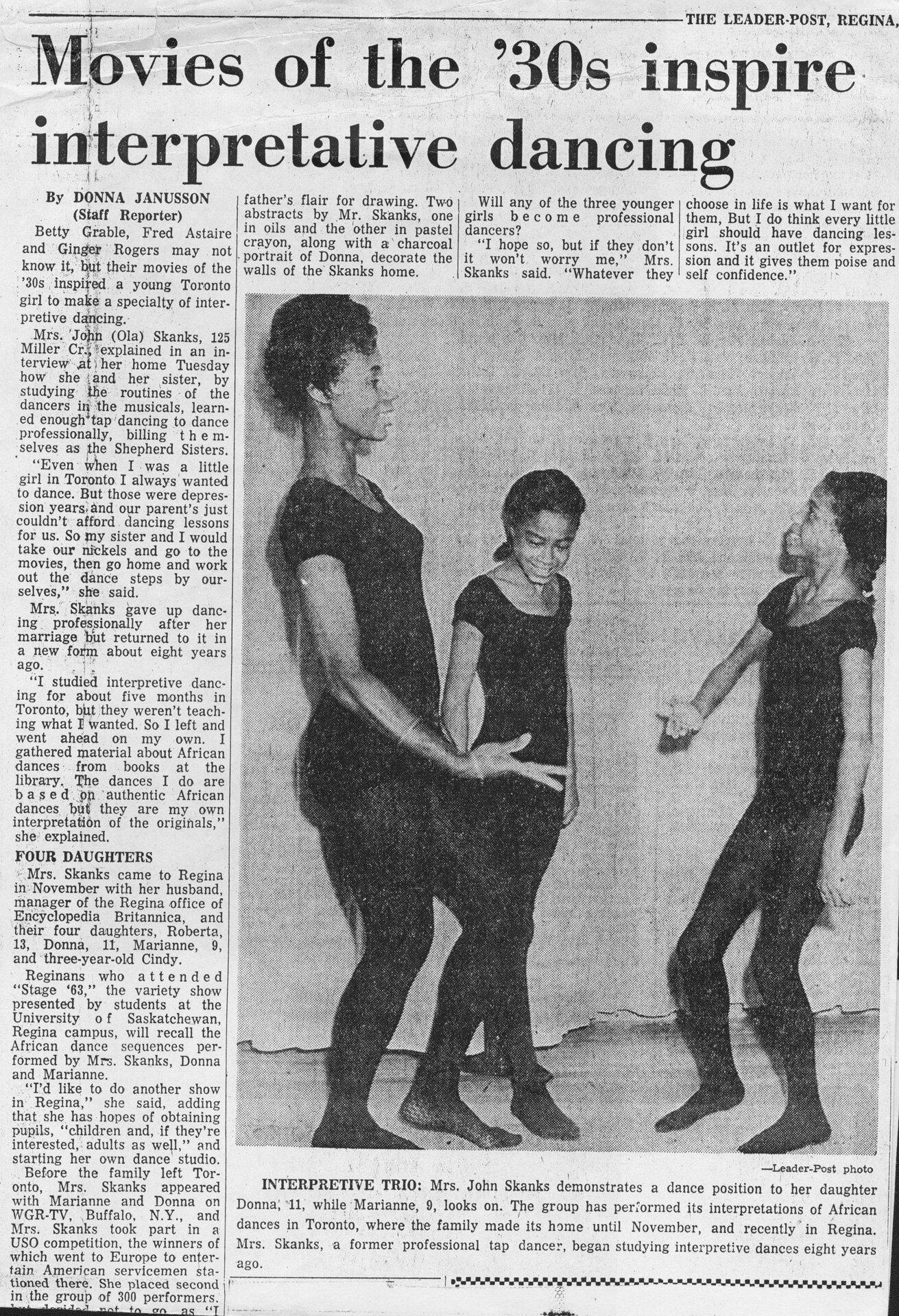

Dance Lessons

Dance, community and integration also overlapped through dance lessons for young people. Lessons in tap and ballet were especially popular and were offered by organizations such as University Settlement House and the Negro Community Centre. Dance lessons at private studios were not open to or financially accessible for many, but there are examples of Black youth training at white studios. This is an area that demands further research so that the history of how dances were transmitted to, by and through Canada’s Black population before 1970 is not lost forever.